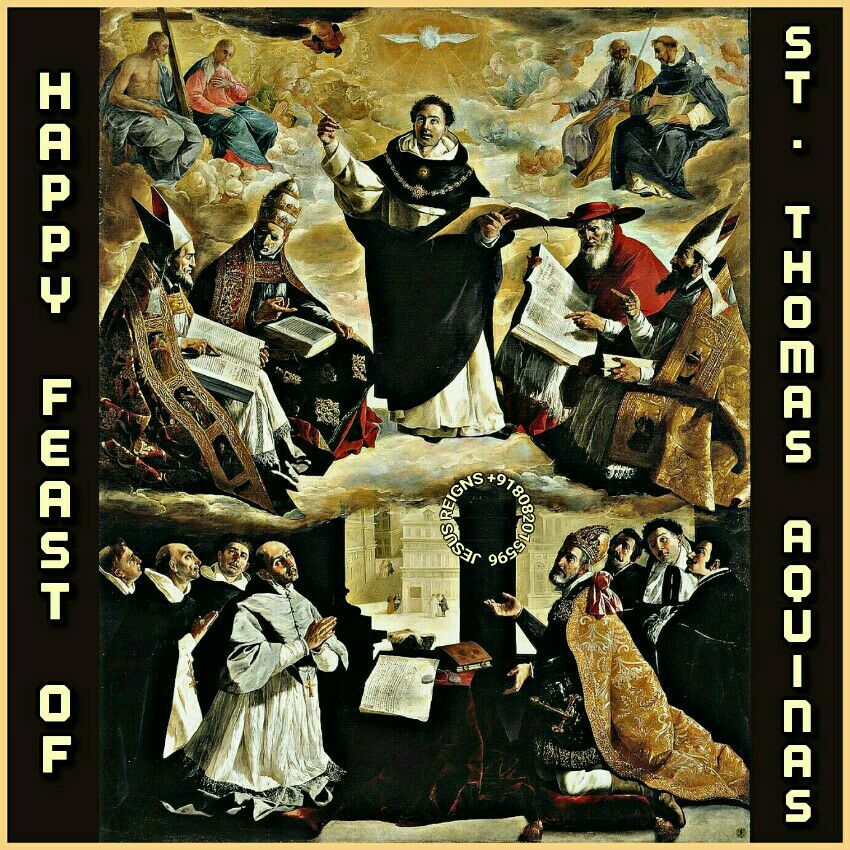

SAINT OF THE DAY

SUNDAY, 28 JANUARY, 2024

SAINT THOMAS AQUINAS

PRIEST AND DOCTOR OF THE CHURCH

(1225 – March 7, 1274)

St. Thomas Aquinas was a Dominican priest and Scriptural theologian. He took seriously the medieval maxim that “grace perfects and builds on nature; it does not set it aside or destroy it.” Therefore, insofar as Thomas thought about philosophy as the discipline that investigates what we can know naturally about God and human beings, he thought that good Scriptural theology, since it treats those same topics, presupposes good philosophical analysis and argumentation. Although Thomas authored some works of pure philosophy, most of his philosophizing is found in the context of his doing Scriptural theology. Indeed, one finds Thomas engaging in the work of philosophy even in his Biblical commentaries and sermons.

Within his large body of work, Thomas treats most of the major sub-disciplines of philosophy, including logic, philosophy of nature, metaphysics, epistemology, philosophical psychology, philosophy of mind, philosophical theology, the philosophy of language, ethics, and political philosophy. As far as his philosophy is concerned, Thomas is perhaps most famous for his so-called five ways of attempting to demonstrate the existence of God. These five short arguments constitute only an introduction to a rigorous project in natural theology—theology that is properly philosophical and so does not make use of appeals to religious authority—that runs through thousands of tightly argued pages. Thomas also offers one of the earliest systematic discussions of the nature and kinds of law, including a famous treatment of natural law. Despite his interest in law, Thomas' writings on ethical theory are actually virtue-centered and include extended discussions of the relevance of happiness, pleasure, the passions, habit, and the faculty of will for the moral life, as well as detailed treatments of each one of the theological, intellectual, and cardinal virtues. Arguably, Thomas' most influential contribution to theology and philosophy, however, is his model for the correct relationship between these two disciplines, a model which has it that neither theology nor philosophy is reduced one to the other, where each of these two disciplines is allowed its own proper scope, and each discipline is allowed to perfect the other, if not in content, then at least by inspiring those who practice that discipline to reach ever new intellectual heights.

In his lifetime, Thomas' expert opinion on theological and philosophical topics was sought by many, including at different times a king, a pope, and a countess. It is fair to say that, as a theologian, Thomas is one of the most important in the history of Western civilization, given the extent of his influence on the development of Roman Catholic theology since the 14th century. However, it also seems right to say—if only from the sheer influence of his work on countless philosophers and intellectuals in every century since the 13th, as well as on persons in countries as culturally diverse as Argentina, Canada, England, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Poland, Spain, and the United States—that, globally, Thomas is one of the 10 most influential philosophers in the Western philosophical tradition.

His works show him to be a brilliant lecturer, a clear thinker and an Aristotelian. In an age which was uncomfortable with the notion that the universe could be known apart from revelation, he pioneered the use of the Greek philosophy that featured the power of reason to demonstrate that God and his universe could be understood by reason guided by faith. His large girth and slow, deliberate style earned him the nickname "The Dumb Ox!"

He was the composer of several memorable religious hymns - O Salutaris Hostia and Pange Lingua being the most familiar to modern worshippers. His extensive writings explored the relationship between the mind of man and the mind of God and his synthesis of knowledge relating to this joining of intellect and religious belief, entitled The Summa Theologica (1267-1273), earned him a lasting reputation among scholars and religious alike. An earlier work, Summa Contra Gentiles (1258 - 1260), is written in a style that attempts to establish the truth of Christian religious belief in arguments addressed to an intelligent, but non-Christian reader.

His proofs for the existence of God, apart from faith and revelation, utilizing the power of reason are considered flawed by some 20th century historians of philosophy (Bertrand Russell, for example) because, he argues, Thomas proved what he already believed to be true. Therefore, according to Russell, his work should be viewed as an artful, concise argument, but not a decisive proof.

In spite of this reservation, Russell acknowledges Thomas's contributions to the intellectual movement called Scholasticism, which succeeded in liberating scholarship from the provincial shackles that uninformed religious censorship often created for it. Thomas also continued in the spirit of Albert the Great to lay a foundation of legitimacy for the Christian study of natural phenomena that allowed Christian Europe to proceed to the initial stages of the scientific revolution. Pope Leo XIII declared Scholasticism in 1879, in the encyclical Aeterni Patris, to be the official Roman Catholic philosophy.

Aquinas' five proofs for the existence of God might be summarized as follows:

1* The unmoved Mover: Whatever is moved, is moved by something, and since an endless regress is not possible, a Prime Mover is required.

2* The first Cause: Every result has a cause and since an endless regress is impossible, there must be a First Cause.

3* The ultimate Necessity: Essentially a repeat of Reason (2.), there must be a source for all consequences which follow.

4* Perfect Source: All perfection in the world requires, as its source, an Ultimate Perfection.

5* Purpose: Even lifeless things have a purpose which must be defined by something outside themselves, since only living things can have an internal purpose.

Thomas's teacher at the University of Paris, Albert the Great, Albertus Magnus, is the man for whom the Aquinas science building is named. Albert is known to have practiced experimental science - his efforts to test the validity of the claims associated with the use of herbal medicines and folk remedies for disease was unusual for his time. Such skepticism, on the part of Albert, was adopted by his pupil, Thomas, and led both men to believe that one could be a sincere Christian and an objective observer of natural phenomena.

The Summa Theologiae, his last and, unfortunately, uncompleted work, deals with the whole of Catholic theology. He stopped work on it after celebrating Mass on December 6, 1273. When asked why he stopped writing, he replied, “I cannot go on…. All that I have written seems to me like so much straw compared to what I have seen and what has been revealed to me.” He died March 7, 1274.

PRAYER: O God, who made Saint Thomas Aquinas outstanding in his zeal for holiness and his study of sacred doctrine, grant us, we pray, that we may understand what he taught and imitate what he accomplished. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

A STUDENT'S PRAYER (BY ST. THOMAS AQUINAS)

Creator of all things,

true Source of light and wisdom,

lofty origin of all being,

graciously let a ray of Your brilliance

penetrate into the darkness of my understanding

and take from me the double darkness

in which I have been born,

an obscurity of both sin and ignorance.

Give me a sharp sense of understanding,

a retentive memory,

and the ability to grasp things correctly and fundamentally.

Grant me the talent of being exact in my explanations,

and the ability to express myself with thoroughness and charm.

Point out the beginning,

direct the progress,

and help in completion;

through Christ our Lord.

Amen.